Mexico Volcanoes

Mexico has 35 Holocene volcanoes. Note that as a scientific organization we provide these listings for informational purposes only, with no international legal or policy implications. Volcanoes will be included on this list if they are within the boundaries of a country, on a shared boundary or area, in a remote territory, or within a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. Bolded volcanoes have erupted within the past 20 years. Suggestions and data updates are always welcome ().

| Volcano Name | Last Eruption | Volcanic Province | Primary Landform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Los Atlixcos | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Shield |

| Barcena | 1953 CE | Mathematicians Ridge Volcanic Province | Minor |

| Ceboruco | 1875 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Chichinautzin | 399 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| El Chichon | 1982 CE | Chiapanecan Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cofre de Perote | 1150 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Colima | 2019 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Comondu-La Purisima | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Las Cumbres | 3920 BCE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Durango Volcanic Field | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| La Gloria | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Los Humeros | 4470 BCE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Caldera |

| Iztaccihuatl | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Jaraguay Volcanic Field | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Jocotitlan | 1270 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| La Malinche | 1170 BCE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Mascota Volcanic Field | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 1952 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Naolinco Volcanic Field | 1200 BCE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Northern EPR at 16°N | 50 BCE | Northern East Pacific Rise Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Northern EPR at 17°N | 50 BCE | Northern East Pacific Rise Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1846 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Pinacate | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Popocatepetl | 2024 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Cerro Prieto | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Minor |

| San Borja Volcanic Field | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Isla San Luis | 1141 BCE | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Minor (Silicic) |

| San Martin | 1796 CE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Sanganguey | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Serdan-Oriental | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Socorro | 1994 CE | Mathematicians Ridge Volcanic Province | Shield |

| Tacana | 1986 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Nevado de Toluca | 1350 BCE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Isla Tortuga | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Shield |

| Zitacuaro-Valle de Bravo | 3050 BCE | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

Chronological listing of known Holocene eruptions (confirmed or uncertain) from volcanoes in Mexico. Bolded eruptions indicate continuing activity.

| Volcano Name | Start Date | Stop Date | Certainty | VEI | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colima | 2019 May 11 | 2019 Jul 12 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 2013 Jan 6 | 2017 Mar 7 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 2005 Jan 9 | 2024 Oct 17 (continuing) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 2004 May 26 | 2004 May 26 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1997 Nov 22 | 2011 Jun 21 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1996 Mar 5 | 2003 Nov 22 (?) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1994 Dec 21 | 1995 Oct 5 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1994 Jul 21 | 1994 Jul 21 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Socorro | 1993 Jan 29 | 1994 Feb 24 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1991 Mar 1 | 1991 Oct 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | [1988 Jun 15 ± 180 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1987 Jul 2 | 1987 Jul 2 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Tacana | 1986 Feb 16 ± 15 days | 1986 Jun 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1985 Jul 2 ± 182 days | 1986 Jan 5 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | [1983 Feb 11] | [1983 Feb 15] | Uncertain | ||

| El Chichon | 1982 Mar 28 | 1982 Sep 11 | Confirmed | 5 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1977 Dec 16 ± 15 days | 1982 Jun 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1975 Dec 11 (?) | 1976 Jun 20 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | [1973 Jan 30] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1963 Jul 2 ± 182 days | 1970 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1961 Jul 2 ± 182 days | 1962 Dec 1 ± 30 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1957 May 14 | 1960 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Barcena | 1952 Aug 1 | 1953 Feb 24 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Socorro | 1951 May 22 | 1951 May 22 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tacana | 1949 Dec 22 | 1950 Jan 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1947 Jan | 1947 Feb | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 1943 Feb 20 | 1952 Feb 25 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1942 | 1943 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | [1941 Apr 15] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Pinacate | [1934 Dec 31] | [1935 Jan 2 (?)] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | 1933 Jan 23 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | [1932 Dec 31 ± 365 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Pinacate | [1928 Jun 9] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1926 ± 4 years | 1931 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1925 | 1927 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1923 Nov 27 | 1924 Mar 7 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1919 Feb 19 (?) | 1922 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1913 Jan 17 | 1913 Jan 24 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1908 Dec 18 | 1909 Jul 1 ± 30 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Socorro | [1905 Jan] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1904 | 1906 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1903 Feb 15 | 1903 Oct 30 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Socorro | [1896] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1893 Dec 4 | 1902 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1891 Jul | 1892 Jun | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1890 Nov 18 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1889 Aug 9 | 1890 Feb 16 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1887 | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1885 Dec 26 | 1886 Oct | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1882 | 1884 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1880 Dec 1 ± 30 days | 1881 Apr 12 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1879 Dec 23 | 1880 Apr 30 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Tacana | 1878 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1875 | 1878 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1874 Jun 12 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1872 Feb 26 | 1873 Mar 27 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Ceboruco | 1870 Feb 21 | 1875 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1870 | 1871 | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1869 Jun 12 | 1869 Aug 24 (in or after) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Tres Virgenes | [1857] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tacana | [1855 Jan 12] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | [1852] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| El Chichon | 1850 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Anthropology | |

| Socorro | [1848] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Pico de Orizaba | 1846 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | [1838] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | [1834] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | [1827] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1819 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1818 Feb 15 | 1818 Feb 16 (?) | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1806 | 1809 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1804 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1802 | 1804 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | [1797] | [1805] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1795 Mar | 1795 Sep | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1794 Aug | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | 1794 May | 1796 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | 1793 Mar 2 | 1793 Dec | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1780 Nov 26 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1771 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1770 Mar 10 | 1770 Mar 12 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1769 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 1759 Sep 29 | 1774 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | [1749] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tres Virgenes | [1746 May 25 ± 15 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Colima | 1744 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1743 Oct 22 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Sanganguey | [1742] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | 1720 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1711 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1697 Oct 20 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1690 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1687 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1666 | 1667 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | 1664 Jan 15 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1663 Oct 13 | 1665 Oct 19 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1642 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1622 Jun 8 | 1622 Jun 9 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1613 | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1611 Apr 15 | 1613 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1606 Nov 25 | 1606 Dec 13 (in or after) | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | [1602] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | 1592 | 1594 Oct | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1590 Jan 14 | 1590 Jan 15 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1590 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1585 Jan 10 | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1580 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1576 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1571 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1569 | 1589 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Ceboruco | 1567 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1566 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1560 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1548 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1545 | 1555 (?) ± 10 years | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1542 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Ceboruco | 1542 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Popocatepetl | 1539 | 1540 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Martin | [1534 (?)] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Pico de Orizaba | [1533] | [1539] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | 1530 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1528 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1519 Sep | 1523 (?) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Colima | 1519 | 1523 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1518 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1512 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | [1509] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | 1504 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | 1488 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Popocatepetl | [1363] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| El Chichon | 1360 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Popocatepetl | 1354 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Pico de Orizaba | [1351] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Popocatepetl | 1345 | 1347 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Jocotitlan | 1270 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1260 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| El Chichon | 1190 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Pico de Orizaba | [1187] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Pico de Orizaba | 1175 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Correlation: Anthropology |

| Pico de Orizaba | [1157] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Cofre de Perote | 1150 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Colima | 1110 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | [1050 ± 50 years] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tacana | 1030 ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Ceboruco | 0930 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 6 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| San Martin | 0890 ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Popocatepetl | 0823 Mar 1 ± 90 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Sidereal: Ice Core |

| El Chichon | 0780 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Colima | 0730 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| El Chichon | 0590 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Colima | 0540 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| El Chichon | 0480 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| San Martin | 0480 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Chichinautzin | 0399 ± 149 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| San Martin | 0380 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Popocatepetl | 0250 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 0220 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Chichinautzin | 0203 ± 131 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| El Chichon | 0190 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 0140 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| San Martin | 0120 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 0090 ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Tacana | 0070 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Pico de Orizaba | 0040 ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| El Chichon | 0020 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Northern EPR at 17°N | 0050 BCE ± 1000 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Magnetism |

| Northern EPR at 16°N | 0050 BCE ± 1000 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Magnetism |

| San Martin | 0150 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Popocatepetl | 0200 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Colima | 0650 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| El Chichon | 0700 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| San Martin | 0750 BCE ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 0780 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Tacana | 1080 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Colima | 1140 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 1140 BCE ± 865 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Isla San Luis | 1141 BCE ± 203 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| La Malinche | 1170 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 1170 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Naolinco Volcanic Field | 1200 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Isla San Luis | 1212 BCE ± 127 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 1320 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| San Martin | 1320 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| El Chichon | 1340 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Nevado de Toluca | 1350 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 1450 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 1500 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 1880 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Popocatepetl | 1890 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 1890 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 1940 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| El Chichon | 2030 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 2050 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Anthropology | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 2110 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| San Martin | 2130 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Chichinautzin | 2238 BCE ± 1413 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Pico de Orizaba | 2300 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Colima | 2370 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Popocatepetl | 2370 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 2500 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Isla San Luis | 2647 BCE ± 128 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 2750 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Pico de Orizaba | 2780 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Colima | 2800 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Colima | 3030 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Zitacuaro-Valle de Bravo | 3050 BCE ± 2000 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: K/Ar |

| Socorro | 3090 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 3180 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Colima | 3270 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Colima | 3350 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| San Martin | 3440 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 3510 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Colima | 3600 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Popocatepetl | 3700 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Las Cumbres | 3920 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 4110 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 4140 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Chichinautzin | 4250 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Colima | 4430 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Los Humeros | 4470 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Colima | 4500 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 4690 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Tacana | 4740 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Colima | 4960 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Popocatepetl | 5150 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| La Malinche | 5580 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Tacana | 5720 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Chichinautzin | 5840 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| La Malinche | 5870 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 5880 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Tacana | 5940 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 5940 BCE ± 335 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| La Malinche | 6120 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 6220 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Popocatepetl | 6250 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| La Malinche | 6310 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 6320 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 6480 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| El Chichon | 6510 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 6710 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| La Malinche | 6710 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| La Malinche | 6890 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 7030 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Popocatepetl | 7150 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Chichinautzin | 7340 BCE ± 1050 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Michoacan-Guanajuato | 7350 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Chichinautzin | 7370 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Colima | 7420 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Pico de Orizaba | 7530 BCE ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Colima | 7690 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Jocotitlan | 7740 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Chichinautzin | 7930 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Tacana | 9450 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

Mexico has 42 Pleistocene volcanoes. Note that as a scientific organization we provide these listings for informational purposes only, with no international legal or policy implications. Volcanoes will be included on this list if they are within the boundaries of a country, on a shared boundary or area, in a remote territory, or within a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. Suggestions and data updates are always welcome ().

| Volcano Name | Volcanic Province | Primary Volcano Type |

|---|---|---|

| Acatlan Volcanic Field | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Caldera |

| Acoculco | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Caldera |

| El Aguajito | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Caldera |

| Aldama Volcanic Field | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Apan-Tezontepec | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Apas-Navenchauc | Chiapanecan Volcanic Arc | Caldera |

| Los Azufres | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Caldera |

| Camargo Volcanic Field | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Volcan el Cantaro | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Coronado | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Composite |

| Los Flores | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Cerro Grande | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Huitepec | Chiapanecan Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Isla Isabel | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Minor |

| Cerro Leon | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Minor |

| Cerro Mencenares | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Minor |

| Mispia | Chiapanecan Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Moctezuma Volcanic Field | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Las Navajas | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Shield |

| Northern Atenguillo | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Northern Guadalajara Mesa | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Papayo | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Minor |

| Poza Rica | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Sierra la Primavera | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Caldera |

| Punta Pulpito | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Minor |

| La Reforma | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Caldera |

| San Ignacio Volcanic Field | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| San Juan | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| San Martin Pajapan | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| San Pedro | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Caldera |

| San Quintin Volcanic Field | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| San Sebastian Volcanic Field | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Santa Maria del Oro | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Minor |

| Santo Domingo Volcanic Field | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Southern Guadalajara | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

| Telapon | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Tepetiltic | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Tequila | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Tlaloc | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Composite |

| Tres Virgenes | Gulf of California Rift Volcanic Province | Composite |

| Ventura Volcanic Field | Basin and Range Volcanic Province | Cluster |

| Los Volcanes | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Cluster |

There are 519 photos available for volcanoes in Mexico.

Los Azufres geothermal field began producing electricity in 1982, the year this photo was taken. The power plant at well AZ-6 shown here is located in the southern (Tejamaniles) section of the field. Surface exposures here consist of the roughly 1-million-year-old Agua Fria rhyolite rocks. Exploratory drilling began at Los Azufres in 1976, and 67 wells had been drilled by 1998 in an area of 60 km2, of which 33 were producing electricity.

Los Azufres geothermal field began producing electricity in 1982, the year this photo was taken. The power plant at well AZ-6 shown here is located in the southern (Tejamaniles) section of the field. Surface exposures here consist of the roughly 1-million-year-old Agua Fria rhyolite rocks. Exploratory drilling began at Los Azufres in 1976, and 67 wells had been drilled by 1998 in an area of 60 km2, of which 33 were producing electricity.Photo by Pat Dobson, 1982 (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory).

Multiple scoria cones have formed across the flanks of Sangangüey. The light-colored cone below the skyline and to the right is cone C4, and the darker cone on the lower right horizon is D8. These two cones are part of the youngest group of cones and may be only 1,000 years old. A lava flow from the C4 crater traveled down the south flank of Sangangüey between the two older cones of B3 and B4, in the foreground.

Multiple scoria cones have formed across the flanks of Sangangüey. The light-colored cone below the skyline and to the right is cone C4, and the darker cone on the lower right horizon is D8. These two cones are part of the youngest group of cones and may be only 1,000 years old. A lava flow from the C4 crater traveled down the south flank of Sangangüey between the two older cones of B3 and B4, in the foreground.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1997 (Smithsonian Institution).

The Río Naolinco lava flow, which fills the entire valley floor in the foreground, is the most voluminous of two chemically distinct lava flows erupted from El Volcancillo on the south flank of Cofre de Perote volcano about 900 years ago. The Río Naolinco flow traveled 50 km and has an estimated volume of about 1.3 km3. This view looks south across the flow near its widest point about 25 km from the vent.

The Río Naolinco lava flow, which fills the entire valley floor in the foreground, is the most voluminous of two chemically distinct lava flows erupted from El Volcancillo on the south flank of Cofre de Perote volcano about 900 years ago. The Río Naolinco flow traveled 50 km and has an estimated volume of about 1.3 km3. This view looks south across the flow near its widest point about 25 km from the vent.Photo by Lee Siebert, 2000 (Smithsonian Institution).

Bárcena volcano forms the elongate island of San Benedicto, seen here from the SW in March 1955. The circular summit crater at the center and the lava delta to the right of the tuff cone formed during an eruption in 1952-53. Pleistocene lava domes are located at the far NE tip of the island. Dark-colored lava from the 1952-53 eruption can be seen in the summit crater.

Bárcena volcano forms the elongate island of San Benedicto, seen here from the SW in March 1955. The circular summit crater at the center and the lava delta to the right of the tuff cone formed during an eruption in 1952-53. Pleistocene lava domes are located at the far NE tip of the island. Dark-colored lava from the 1952-53 eruption can be seen in the summit crater.Photo by Adrian Richards, 1955 (U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office).

Parícutin cinder cone, born in a Mexican cornfield in 1943, is perhaps the world's best-known example of a pyroclastic cone. Pyroclastic cones (from the Greek words for "fire" and "broken") are created by the accumulation of explosively ejected fragmental material around a volcanic vent. Depending on the dominant type of ejecta, they are called cinder cones, scoria cones, pumice cones, ash cones, or tuff cones. Pyroclastic cones are typically tens of meters to several hundred meters high and often issue lava flows from vents at their base.

Parícutin cinder cone, born in a Mexican cornfield in 1943, is perhaps the world's best-known example of a pyroclastic cone. Pyroclastic cones (from the Greek words for "fire" and "broken") are created by the accumulation of explosively ejected fragmental material around a volcanic vent. Depending on the dominant type of ejecta, they are called cinder cones, scoria cones, pumice cones, ash cones, or tuff cones. Pyroclastic cones are typically tens of meters to several hundred meters high and often issue lava flows from vents at their base.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1981.

Tacaná is located on the México/Guatemala border at the far NW end of the Central American volcanic belt. It is seen here from the Guatemalan side of the border to the ENE, where it rises steeply above a 9-km-wide caldera surrounded by deeply eroded plutonic rocks. Historical activity has included mild phreatic eruptions, but stronger explosive activity and production of pyroclastic flows occurred earlier.

Tacaná is located on the México/Guatemala border at the far NW end of the Central American volcanic belt. It is seen here from the Guatemalan side of the border to the ENE, where it rises steeply above a 9-km-wide caldera surrounded by deeply eroded plutonic rocks. Historical activity has included mild phreatic eruptions, but stronger explosive activity and production of pyroclastic flows occurred earlier.Photo by Bill Rose, 1986 (Michigan Technological University).

An aerial view of the Río Las Majadas valley in Guatemala on the NNE side of Tacaná volcano shows thick deposits of lahars and debris avalanches filling the valley. These deposits provide a flat surface for agricultural use in deeply eroded terrain. The valley drains from its headwaters in Guatemala through México into the Pacific Ocean, and lahars during future eruptions could affect both countries.

An aerial view of the Río Las Majadas valley in Guatemala on the NNE side of Tacaná volcano shows thick deposits of lahars and debris avalanches filling the valley. These deposits provide a flat surface for agricultural use in deeply eroded terrain. The valley drains from its headwaters in Guatemala through México into the Pacific Ocean, and lahars during future eruptions could affect both countries.Photo by Bill Rose, 1986 (Michigan Technological University).

A weak plume from the summit of Mexico's Colima volcano in 1992 with snow-capped Nevado de Colima to the left; view from the WSW. Frequent eruptions have been recorded at Colima since the 16th century. Eruptions have been dominated during the past century by lava effusion associated with lava dome growth, explosive eruptions of varying magnitude, and frequent pyroclastic flows.

A weak plume from the summit of Mexico's Colima volcano in 1992 with snow-capped Nevado de Colima to the left; view from the WSW. Frequent eruptions have been recorded at Colima since the 16th century. Eruptions have been dominated during the past century by lava effusion associated with lava dome growth, explosive eruptions of varying magnitude, and frequent pyroclastic flows.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1992 (Smithsonian Institution).

A symmetrical cone is located on Volcán Pelado, a small shield volcano about 10 km south of Xitle volcano. Pyroclastic flows accompanied the formation of the cone. Pelado and the Xitle cone, which erupted about 1,670 years ago, are among the many Holocene vents of the Chichinautzin volcanic field. Both eruptions affected nearby settlements.

A symmetrical cone is located on Volcán Pelado, a small shield volcano about 10 km south of Xitle volcano. Pyroclastic flows accompanied the formation of the cone. Pelado and the Xitle cone, which erupted about 1,670 years ago, are among the many Holocene vents of the Chichinautzin volcanic field. Both eruptions affected nearby settlements.Photo by Paul Wallace, 1991 (University of California Berkeley).

The unvegetated Ceboruco lava flow in the foreground appears to be some of the youngest of the W-flank flows. The peaks on either side of the broad summit in this view from the WSW are the rims of the 4-km-wide outer caldera.

The unvegetated Ceboruco lava flow in the foreground appears to be some of the youngest of the W-flank flows. The peaks on either side of the broad summit in this view from the WSW are the rims of the 4-km-wide outer caldera.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1997 (Smithsonian Institution).

Volcán el Puerto (left) and Volcán Embarcadero (right) are seen from the east across fields of the Mascota graben. Both cones have craters that open towards the east. They are in the NW side of the Mascota Volcanic Field and erupted near the western base of the graben walls, which in this view consists of metamorphic rocks and elsewhere of Cretaceous tuffs. The Mascota graben here is about 5 km wide.

Volcán el Puerto (left) and Volcán Embarcadero (right) are seen from the east across fields of the Mascota graben. Both cones have craters that open towards the east. They are in the NW side of the Mascota Volcanic Field and erupted near the western base of the graben walls, which in this view consists of metamorphic rocks and elsewhere of Cretaceous tuffs. The Mascota graben here is about 5 km wide.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1985 (Smithsonian Institution).

A cluster of cinder cones of the Camargo volcanic field lies within the arid northern Bolsón de Mapimí graben in north-central México, about 150 km SW of Big Bend National Park in Texas. More than 300 volcanic vents, mostly cinder cones and lava cones, are located in a broad 2500 km2 lava plateau that extends 60 km E-W and 70 km N-S. The Camargo field is mostly Pliocene in age, but activity continued into the Pleistocene.

A cluster of cinder cones of the Camargo volcanic field lies within the arid northern Bolsón de Mapimí graben in north-central México, about 150 km SW of Big Bend National Park in Texas. More than 300 volcanic vents, mostly cinder cones and lava cones, are located in a broad 2500 km2 lava plateau that extends 60 km E-W and 70 km N-S. The Camargo field is mostly Pliocene in age, but activity continued into the Pleistocene.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1996 (Smithsonian Institution).

Pyroclastic surge deposits from La Breña maar in México's Durango volcanic field show both laminar and dune bedding. The thin beds (pen in the center for scale) were created by successive explosive eruptions that produced high-velocity pyroclastic surges that swept radially away from the volcano. The direction of movement of the surge clouds was from right to left, as seen from the truncated dune beds on the near-vent side.

Pyroclastic surge deposits from La Breña maar in México's Durango volcanic field show both laminar and dune bedding. The thin beds (pen in the center for scale) were created by successive explosive eruptions that produced high-velocity pyroclastic surges that swept radially away from the volcano. The direction of movement of the surge clouds was from right to left, as seen from the truncated dune beds on the near-vent side.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1988 (Smithsonian Institution).

A geologist stands on the irregular surface of a lava flow north of Volcán la Morusa, near Cerro Colorado. The flow is one of many young sparsely vegetated basaltic lava flows of the Pinacate volcanic field. Flow morphologies remain pristine for long periods of time in this arid region.

A geologist stands on the irregular surface of a lava flow north of Volcán la Morusa, near Cerro Colorado. The flow is one of many young sparsely vegetated basaltic lava flows of the Pinacate volcanic field. Flow morphologies remain pristine for long periods of time in this arid region.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1996 (Smithsonian Institution).

This photo shows an ash plume rising above Parícutin on 9 June 1943, seen here from the Uruapan highway to the east. Prevailing winds distribute the ash plume to the south. Other scoria cones appear on the horizon, some of the 1,000-plus scoria cones within the massive Michoacán-Guanajuato volcanic field.

This photo shows an ash plume rising above Parícutin on 9 June 1943, seen here from the Uruapan highway to the east. Prevailing winds distribute the ash plume to the south. Other scoria cones appear on the horizon, some of the 1,000-plus scoria cones within the massive Michoacán-Guanajuato volcanic field.Photo by William Foshag, 1943 (Smithsonian Institution).

On 7 July 1944 a lava flow (left) approaches the church of San Juan Parangaricutiro. Residents had already evacuated the town when lava first entered the town on 17 June. By the time the flow stopped in early August the church was entirely surrounded by lava.

On 7 July 1944 a lava flow (left) approaches the church of San Juan Parangaricutiro. Residents had already evacuated the town when lava first entered the town on 17 June. By the time the flow stopped in early August the church was entirely surrounded by lava.Photo by William Foshag, 1943 (Smithsonian Institution, published in Luhr and Simkin, 1993).

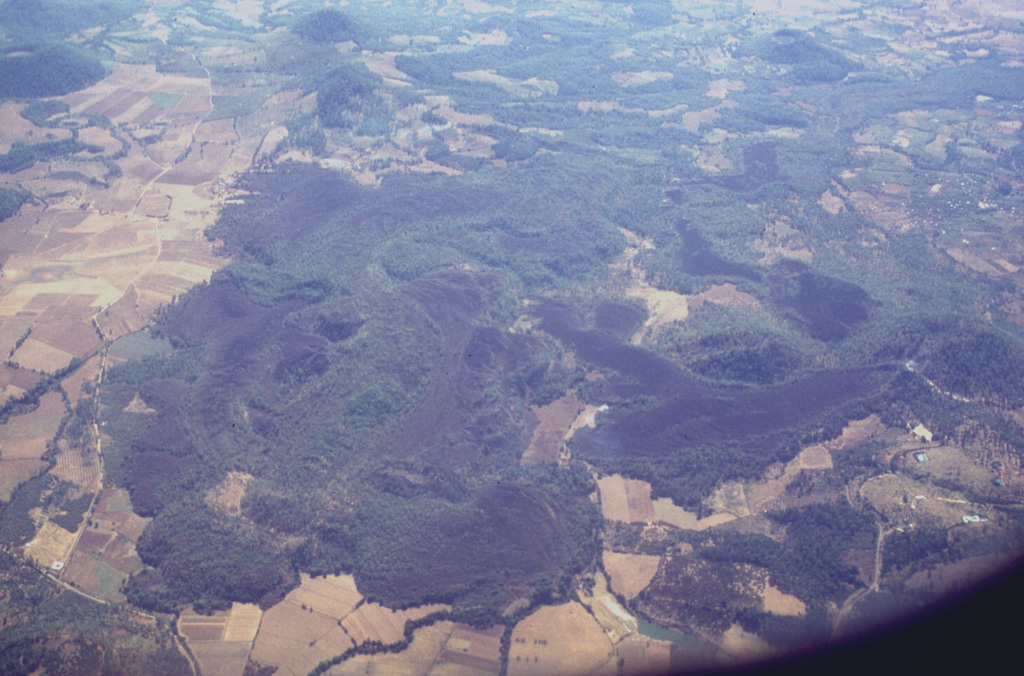

Jorullo volcano and associated lava flows in the Michoacan-Guanajuato volcanic field are visible in the bottom of this photo. Four NE-SW-trending vents flank the main cone, which erupted during 1759-1774. The 1759-74 lava flows appear in varying shades of gray, with the initial (and largest) flows being lighter in color (due to partial ash cover), and the most recent ash-free lava being darker and extending to the NW and NE. Jorullo lies about 80 km SE of Parícutin.

Jorullo volcano and associated lava flows in the Michoacan-Guanajuato volcanic field are visible in the bottom of this photo. Four NE-SW-trending vents flank the main cone, which erupted during 1759-1774. The 1759-74 lava flows appear in varying shades of gray, with the initial (and largest) flows being lighter in color (due to partial ash cover), and the most recent ash-free lava being darker and extending to the NW and NE. Jorullo lies about 80 km SE of Parícutin. Aerial photo by Comisión de Estudios del Territorio Nacional (CETENAL).

The Cerro Papayo dacite lava dome is located 2.5 km S of the pass in the northern Sierra Nevada between Mexico City and Puebla. The 1-km-wide dome rises 230 m above surrounding lava flows and produced voluminous lava flows that traveled about 10 km ENE toward the Puebla basin and 10 km WSW into the Valley of Mexico.

The Cerro Papayo dacite lava dome is located 2.5 km S of the pass in the northern Sierra Nevada between Mexico City and Puebla. The 1-km-wide dome rises 230 m above surrounding lava flows and produced voluminous lava flows that traveled about 10 km ENE toward the Puebla basin and 10 km WSW into the Valley of Mexico.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1999 (Smithsonian Institution).

The renowned church of San Juan Parangaricutiro was surrounded by lava flows from Parícutin in July 1944. Only one of the two church steeples had been completed prior to the eruption. The interior of the church was dismantled only days before it was overrun by the lava flow. The west margin of the 1944 lava flow appears at the top, with faintly visible abandoned streets of the town beyond.

The renowned church of San Juan Parangaricutiro was surrounded by lava flows from Parícutin in July 1944. Only one of the two church steeples had been completed prior to the eruption. The interior of the church was dismantled only days before it was overrun by the lava flow. The west margin of the 1944 lava flow appears at the top, with faintly visible abandoned streets of the town beyond. Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1981 (published in Luhr and Simkin, 1993).

This view from the west on 4 November 1982 shows the impact of the El Chichón eruption about seven months later. Fumaroles are present around the new lake partially filling the crater, and the surrounding area was devastated by pyroclastic flows and surges. The 1982 crater is located within an older 1.5 x 1.9 km crater.

This view from the west on 4 November 1982 shows the impact of the El Chichón eruption about seven months later. Fumaroles are present around the new lake partially filling the crater, and the surrounding area was devastated by pyroclastic flows and surges. The 1982 crater is located within an older 1.5 x 1.9 km crater.NASA Space Shuttle image, 1982 (http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/).

El Chichón is a small, but powerful andesitic stratovolcano that occupies an isolated location in the Chiapas region far from other Holocene volcanoes. Prior to 1982, this relatively unknown volcano was a heavily forested lava dome cluster of no greater height than adjacent non-volcanic peaks. This 1983 photo from the NE shows the effects of powerful eruptions in 1982, the first major eruptions at El Chichón in 500 years. The explosions removed the summit lava dome and created a new 1-km-wide crater now containing an acidic lake.

El Chichón is a small, but powerful andesitic stratovolcano that occupies an isolated location in the Chiapas region far from other Holocene volcanoes. Prior to 1982, this relatively unknown volcano was a heavily forested lava dome cluster of no greater height than adjacent non-volcanic peaks. This 1983 photo from the NE shows the effects of powerful eruptions in 1982, the first major eruptions at El Chichón in 500 years. The explosions removed the summit lava dome and created a new 1-km-wide crater now containing an acidic lake.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1983.

Pico de Orizaba volcano is seen here from the south, with snow-free Sierra Negra volcano to its left. Sierra Negra is the southernmost major vent of the roughly NNE-SSW-trending Pico de Orizaba-Cofre de Perote volcanic chain. The construction of Sierra Negra was contemporaneous with the mid-Pleistocene early stages in the formation of Orizaba volcano. Sierra Negra is composed largely of lava flows and produced numerous pyroclastic flows mainly to the SW and W.

Pico de Orizaba volcano is seen here from the south, with snow-free Sierra Negra volcano to its left. Sierra Negra is the southernmost major vent of the roughly NNE-SSW-trending Pico de Orizaba-Cofre de Perote volcanic chain. The construction of Sierra Negra was contemporaneous with the mid-Pleistocene early stages in the formation of Orizaba volcano. Sierra Negra is composed largely of lava flows and produced numerous pyroclastic flows mainly to the SW and W.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

A small explosion 8 February 1999 produced a plume of gas and minor ash that is seen here from the SE about 5 seconds after the explosion began. Rapid lava extrusion began on 20 November 1998 and produced a lava dome in the 1994 crater that soon flowed over the crater rim, producing lava flows that descended the SW flank in several lobes. Block-and-ash flows from collapse of the flow fronts traveled down SW flank drainages. Periodic larger explosions occurred later during this eruption.

A small explosion 8 February 1999 produced a plume of gas and minor ash that is seen here from the SE about 5 seconds after the explosion began. Rapid lava extrusion began on 20 November 1998 and produced a lava dome in the 1994 crater that soon flowed over the crater rim, producing lava flows that descended the SW flank in several lobes. Block-and-ash flows from collapse of the flow fronts traveled down SW flank drainages. Periodic larger explosions occurred later during this eruption.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1999 (Smithsonian Institution).

The summit ridge of flat-topped Volcán Molcajete (left) is at the level of the horizon in this view from the SW. Molcajete, referring to stone bowls used for grinding grains, is a common name applied to scoria cones with well-preserved craters. Volcán El Tecomate is the steep-sided scoria cone to the right. These two cones are located NE of the town of Mascota and are part of a Pleistocene-to-Holocene volcanic field in the Jalisco block, which is being underthrust by the eastward-subducting Rivera tectonic plate.

The summit ridge of flat-topped Volcán Molcajete (left) is at the level of the horizon in this view from the SW. Molcajete, referring to stone bowls used for grinding grains, is a common name applied to scoria cones with well-preserved craters. Volcán El Tecomate is the steep-sided scoria cone to the right. These two cones are located NE of the town of Mascota and are part of a Pleistocene-to-Holocene volcanic field in the Jalisco block, which is being underthrust by the eastward-subducting Rivera tectonic plate.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1985 (Smithsonian Institution).

A geologist observes an ash plume rising above the crater of Parícutin on 22 March 1944, as seen from 1 km SW at Mesa de Cocjarao. During March 1944 the eruptive activity ranged from small ash plumes accompanied by deep rumbling to large but almost soundless ash plumes, as was true with the plume shown here.

A geologist observes an ash plume rising above the crater of Parícutin on 22 March 1944, as seen from 1 km SW at Mesa de Cocjarao. During March 1944 the eruptive activity ranged from small ash plumes accompanied by deep rumbling to large but almost soundless ash plumes, as was true with the plume shown here.Photo by William Foshag, 1944 (Smithsonian Institution, published in Foshag and Gonzáles-Reyna, 1956).

The bedded deposits at the base of this outcrop on the SW flank of Colima near the village of San Antonio are pyroclastic flow and pyroclastic surge deposits from an eruption that was radiocarbon dated to about 4,300 years ago. The thick deposit forming the majority of the outcrop is a debris avalanche deposit produced by collapse of the volcano. Erosion at the base of this deposit has exposed its mottled internal texture, reflecting various lithologic units that were transported without being mixed together.

The bedded deposits at the base of this outcrop on the SW flank of Colima near the village of San Antonio are pyroclastic flow and pyroclastic surge deposits from an eruption that was radiocarbon dated to about 4,300 years ago. The thick deposit forming the majority of the outcrop is a debris avalanche deposit produced by collapse of the volcano. Erosion at the base of this deposit has exposed its mottled internal texture, reflecting various lithologic units that were transported without being mixed together.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1983 (Smithsonian Institution).

Following the eruption of the Tepic Pumice and the formation of an elongated caldera at the summit of San Juan volcano, a lava dome was constructed within the caldera. The dome forms the rounded forested area in front of the western caldera rim, which marks the horizon. The caldera is 4 km wide in the E-W direction of this photo and 1 km wide in a N-S direction. Andesitic lava flows (left center) erupted from the dome and flowed across the caldera floor to its eastern side.

Following the eruption of the Tepic Pumice and the formation of an elongated caldera at the summit of San Juan volcano, a lava dome was constructed within the caldera. The dome forms the rounded forested area in front of the western caldera rim, which marks the horizon. The caldera is 4 km wide in the E-W direction of this photo and 1 km wide in a N-S direction. Andesitic lava flows (left center) erupted from the dome and flowed across the caldera floor to its eastern side.Photo by Jim Luhr, 1979 (Smithsonian Institution).

Isla San Luis lies across a narrow channel from the NE coast of Baja California (in the background). A rhyolite obsidian dome is in the center of the small island. An older dome forms the northern part of the island (foreground) and is partially mantled by ash and pumice from the central dome. An eroded tuff ring, Plaza de Toros, occupies the SE end of the island.

Isla San Luis lies across a narrow channel from the NE coast of Baja California (in the background). A rhyolite obsidian dome is in the center of the small island. An older dome forms the northern part of the island (foreground) and is partially mantled by ash and pumice from the central dome. An eroded tuff ring, Plaza de Toros, occupies the SE end of the island.Photo by Keith Sutter, 2000.

The eastern side of the Volcán el Cántaro complex, seen here from Volcán Apaxtepec, a cinder cone NE of Nevado de Colima volcano, rises above the floor of the Colima rift zone. Cántaro is the oldest and northernmost volcano of the Cántaro-Colima volcanic complex, which extends south through Nevado de Colima to the historically active Volcán de Colima. Cántaro is erosionally modified, but has many well-preserved andesitic-dacitic lava domes on its northern and eastern flanks, including Cerro el Capulín on the far right horizon.

The eastern side of the Volcán el Cántaro complex, seen here from Volcán Apaxtepec, a cinder cone NE of Nevado de Colima volcano, rises above the floor of the Colima rift zone. Cántaro is the oldest and northernmost volcano of the Cántaro-Colima volcanic complex, which extends south through Nevado de Colima to the historically active Volcán de Colima. Cántaro is erosionally modified, but has many well-preserved andesitic-dacitic lava domes on its northern and eastern flanks, including Cerro el Capulín on the far right horizon. Photo by Lee Siebert, 2000 (Smithsonian Institution).

The large, steep-sided Xicomulco lava flow descends from the flanks of the Sierra Chichinautzin into the Valley of Mexico. The viscous lava flow averages 75 m in thickness, displays prominent flow levees, and traveled 4.5 km north. The flow was extruded with very little explosive activity and the vent was subsequently filled in and is now overlain by the town of San Bartolo Xicomulco (right-center). In the background is the town of San Pablo Oztotepec. Volcán Tlaloc is the broad volcano in the center of the horizon.

The large, steep-sided Xicomulco lava flow descends from the flanks of the Sierra Chichinautzin into the Valley of Mexico. The viscous lava flow averages 75 m in thickness, displays prominent flow levees, and traveled 4.5 km north. The flow was extruded with very little explosive activity and the vent was subsequently filled in and is now overlain by the town of San Bartolo Xicomulco (right-center). In the background is the town of San Pablo Oztotepec. Volcán Tlaloc is the broad volcano in the center of the horizon.Photo by Gerardo Carrasco-Núñez, 1997 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

The steep margin of a thick basaltic andesite lava flow is seen from near State Highway 1 in central Baja California with a vehicle for scale. The sparsely vegetated flow is of probable Holocene age and is one of many recent lava flows of the San Borja Volcanic Field.

The steep margin of a thick basaltic andesite lava flow is seen from near State Highway 1 in central Baja California with a vehicle for scale. The sparsely vegetated flow is of probable Holocene age and is one of many recent lava flows of the San Borja Volcanic Field.Photo by Andy Saunders, 1984 (University of Leichester).

The eroded Sangangüey edifice was constructed during the Pleistocene and its flanks contain 45 scoria cones, some of which have erupted during the Holocene. The cone forming the peak on the lower right horizon and the cone highlighted by the sun below and to the right of the summit in this view from the south are among the youngest.

The eroded Sangangüey edifice was constructed during the Pleistocene and its flanks contain 45 scoria cones, some of which have erupted during the Holocene. The cone forming the peak on the lower right horizon and the cone highlighted by the sun below and to the right of the summit in this view from the south are among the youngest.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1997 (Smithsonian Institution).

An ash plume rises from the summit crater of Parícutin sometime during 1946-48. A thick ash deposit covers the foreground. An estimated 4,500 cattle and 550 horses died during the heavy ashfall in the early months of the eruption, devastating the local people who depended on the animals for food, plowing, and transportation. Ashfall was deeper than 15 cm over a 300 km2 area around the volcano and continued with varying intensity throughout the 9-year-long eruption.

An ash plume rises from the summit crater of Parícutin sometime during 1946-48. A thick ash deposit covers the foreground. An estimated 4,500 cattle and 550 horses died during the heavy ashfall in the early months of the eruption, devastating the local people who depended on the animals for food, plowing, and transportation. Ashfall was deeper than 15 cm over a 300 km2 area around the volcano and continued with varying intensity throughout the 9-year-long eruption.Photo by Ray Wilcox (U.S. Geological Survey).

El Aguajito caldera is located along the Gulf of California immediately NE of Tres Vírgenes volcano (lower left) and NW of La Reforma caldera (partially visible at the right). The approximately 10-km-wide caldera covers the broad dissected area from Tres Vírgenes to the sea. The rim of the mid-Pleistocene caldera is not exposed, but an arcuate line of andesitic-to-rhyolitic lava domes lies along its northern margin. Hot springs are located along the southern caldera margin in the linear NW-trending valley between the caldera and Tres Vírgenes.

El Aguajito caldera is located along the Gulf of California immediately NE of Tres Vírgenes volcano (lower left) and NW of La Reforma caldera (partially visible at the right). The approximately 10-km-wide caldera covers the broad dissected area from Tres Vírgenes to the sea. The rim of the mid-Pleistocene caldera is not exposed, but an arcuate line of andesitic-to-rhyolitic lava domes lies along its northern margin. Hot springs are located along the southern caldera margin in the linear NW-trending valley between the caldera and Tres Vírgenes.NASA Landsat image (processed by Brian Hausback, UC Sacramento).

Tacaná is located along the México/Guatemala border, seen here from the SSE from the Mexican town of Unión Juárez, where it rises above the Pacific coastal plain. The elongate summit region is composed of a series of lava domes. Historical activity has included mild phreatic eruptions, but stronger explosive activity, and production of pyroclastic flows, occurred earlier.

Tacaná is located along the México/Guatemala border, seen here from the SSE from the Mexican town of Unión Juárez, where it rises above the Pacific coastal plain. The elongate summit region is composed of a series of lava domes. Historical activity has included mild phreatic eruptions, but stronger explosive activity, and production of pyroclastic flows, occurred earlier.Photo by Norm Banks, 1987 (U.S. Geological Survey).

Broad alluvial fans composed of fluvial, glacial, and volcaniclastic sediments surround La Malinche volcano. The circular volcano is dissected by radial drainages on all sides. During attempts to reconstruct the Quaternary glacial history of Mexican volcanoes a yellowish-red pumice layer that extends around Malinche volcano was dated to between about 12,100 and 7,650 years old.

Broad alluvial fans composed of fluvial, glacial, and volcaniclastic sediments surround La Malinche volcano. The circular volcano is dissected by radial drainages on all sides. During attempts to reconstruct the Quaternary glacial history of Mexican volcanoes a yellowish-red pumice layer that extends around Malinche volcano was dated to between about 12,100 and 7,650 years old.Photo by Gerardo Carrasco-Núñez, 1997 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

This view from the SE shows the Tres Vírgenes volcanic group, which is aligned in a SW-NE direction. Volcanism has migrated to the SW from the oldest peak El Viejo (far right) through El Volcán Azufre to La Vírgen (center), the highest peak. The ridges on the left flank of La Vírgen are rhyodacite lava flows from a major eruption; the smooth hills in the foreground are Quaternary ignimbrite sheets probably related to the Pleistocene La Reforma caldera to the east.

This view from the SE shows the Tres Vírgenes volcanic group, which is aligned in a SW-NE direction. Volcanism has migrated to the SW from the oldest peak El Viejo (far right) through El Volcán Azufre to La Vírgen (center), the highest peak. The ridges on the left flank of La Vírgen are rhyodacite lava flows from a major eruption; the smooth hills in the foreground are Quaternary ignimbrite sheets probably related to the Pleistocene La Reforma caldera to the east. Photo by José Macías, 1995 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

The summit depression of Tequila volcano is breached narrowly to the NE and originated from erosional excavation. A prominent 300-m-high dacitic spine, left after erosional removal of softer rocks surrounding the vent, forms the dramatic steep-sided peak at the left. The spine was dated at about 210,000 years and probably represents the latest activity from the central vent.

The summit depression of Tequila volcano is breached narrowly to the NE and originated from erosional excavation. A prominent 300-m-high dacitic spine, left after erosional removal of softer rocks surrounding the vent, forms the dramatic steep-sided peak at the left. The spine was dated at about 210,000 years and probably represents the latest activity from the central vent. Photo by Jim Luhr, 1979 (Smithsonian Institution).

The middle unit of the La Vírgen Plinian fall deposit displays a massive structure (lacking internal structure) with large pink pumice fragments. This deposit, more than 1 km3, is the product of a major explosive eruption that occurred from Tres Vírgenes volcano. The dispersal axis of this airfall deposit was to the SW. The eruption also included the emplacement of pyroclastic flows and voluminous lava flows.

The middle unit of the La Vírgen Plinian fall deposit displays a massive structure (lacking internal structure) with large pink pumice fragments. This deposit, more than 1 km3, is the product of a major explosive eruption that occurred from Tres Vírgenes volcano. The dispersal axis of this airfall deposit was to the SW. The eruption also included the emplacement of pyroclastic flows and voluminous lava flows.Photo by José Macías, 1995 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

The Popocatépetl summit crater is seen here from the NW on 16 June 1997. The irregular crater floor has several vents and some active fumaroles. The photo was taken five days after an ash eruption on 11 June that produced a 4-km-high plume and was accompanied by lahars that reached several towns to the east. Another strong explosion on 30 June was followed by lava extrusion on the crater floor.

The Popocatépetl summit crater is seen here from the NW on 16 June 1997. The irregular crater floor has several vents and some active fumaroles. The photo was taken five days after an ash eruption on 11 June that produced a 4-km-high plume and was accompanied by lahars that reached several towns to the east. Another strong explosion on 30 June was followed by lava extrusion on the crater floor.Photo by Roberto Quass, 1997 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

The N-S-trending Popocatépetl-Iztaccíhuatl volcanic chain lies between the Valley of Mexico and the Puebla basin. Snow-capped Iztaccíhuatl volcano lies just above the center of the image. The city of Texmelucan can be seen at the upper right. Across the Paso de Cortés from Iztaccíhuatl is steaming Popocatépetl volcano, located SE of the city of Amecameca (mid-left margin). A voluminous prehistorical lava field from Popocatépetl forms the forested lobe extending about 20 km down the eastern flank at the lower right.

The N-S-trending Popocatépetl-Iztaccíhuatl volcanic chain lies between the Valley of Mexico and the Puebla basin. Snow-capped Iztaccíhuatl volcano lies just above the center of the image. The city of Texmelucan can be seen at the upper right. Across the Paso de Cortés from Iztaccíhuatl is steaming Popocatépetl volcano, located SE of the city of Amecameca (mid-left margin). A voluminous prehistorical lava field from Popocatépetl forms the forested lobe extending about 20 km down the eastern flank at the lower right.ASTER satellite image, 2001 (National Aeronautical and Space Administration, processed by Doug Edmonds).

The western flank of Popocatépetl is seen here in November 1994, a little more than a month prior to its eruption on 21 December 1994. A faint gas plume is dispersing to the NE by predominant winds. The peak halfway down the left flank is Ventorrillo, a remnant of an older volcanic center preceding the construction of the modern edifice.

The western flank of Popocatépetl is seen here in November 1994, a little more than a month prior to its eruption on 21 December 1994. A faint gas plume is dispersing to the NE by predominant winds. The peak halfway down the left flank is Ventorrillo, a remnant of an older volcanic center preceding the construction of the modern edifice.Photo by José Macías, 1994 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

The low-angle La Laja shield volcano lies at the southern end of the Plio-Pleistocene Northern Atenguillo volcanic field in the Jalisco tectonic block of western México. La Laja was dated at about 660,000 years. Initial phreatomagmatic eruptions at La Laja produced pyroclastic-surge and airfall deposits. These were followed by the extrusion of a thick sequence of lava flows that built the symmetrical shield volcano. The flows blocked the Río Atenguillo, forming an ephemeral 20-km-long lake.

The low-angle La Laja shield volcano lies at the southern end of the Plio-Pleistocene Northern Atenguillo volcanic field in the Jalisco tectonic block of western México. La Laja was dated at about 660,000 years. Initial phreatomagmatic eruptions at La Laja produced pyroclastic-surge and airfall deposits. These were followed by the extrusion of a thick sequence of lava flows that built the symmetrical shield volcano. The flows blocked the Río Atenguillo, forming an ephemeral 20-km-long lake.Photo by Paul Wallace, 1998 (University of California Berkeley).

The NW-most of the two Las Derrumbadas lava domes is surrounded by hummocky debris avalanche deposits such as those in the foreground, that were produced by repeated collapse of the domes. The hummocks contain mixtures of rock types, including pyroclastic surge deposits, Cretaceous limestones, lacustrine sediments, and banded obsidians. These are thought to have originated from a former tuff ring that surrounded the lava domes.

The NW-most of the two Las Derrumbadas lava domes is surrounded by hummocky debris avalanche deposits such as those in the foreground, that were produced by repeated collapse of the domes. The hummocks contain mixtures of rock types, including pyroclastic surge deposits, Cretaceous limestones, lacustrine sediments, and banded obsidians. These are thought to have originated from a former tuff ring that surrounded the lava domes.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1997 (Smithsonian Institution).

One of the first photographs taken of the Parícutin eruption shows an ash plume rising from the new volcano at 1800 on 20 February 1943, 1.5 hours after the start of the eruption. The photo was taken near Ticuiro, 5 km NNW of the volcano, with the fields of San Juan Parangaricutiro, later overrun by lava flows, in the foreground. Cerro de Canicjuata is the forested older cone to the right.

One of the first photographs taken of the Parícutin eruption shows an ash plume rising from the new volcano at 1800 on 20 February 1943, 1.5 hours after the start of the eruption. The photo was taken near Ticuiro, 5 km NNW of the volcano, with the fields of San Juan Parangaricutiro, later overrun by lava flows, in the foreground. Cerro de Canicjuata is the forested older cone to the right.Photo by Luis Mora-Garcia, 1943 (published in Foshag and González-Reyna, 1956).

The wrinkled surface of a pahoehoe lava flow of Los Flores volcanic field is exposed near the town of Nuevo Morelos. The basaltic lava flow, seen here about 35 km from its source at Cerro Partido, traveled about 80 km to the SSE down a narrow valley in the Sierra Madre Oriental. The geologic hammer at the lower right provides scale.

The wrinkled surface of a pahoehoe lava flow of Los Flores volcanic field is exposed near the town of Nuevo Morelos. The basaltic lava flow, seen here about 35 km from its source at Cerro Partido, traveled about 80 km to the SSE down a narrow valley in the Sierra Madre Oriental. The geologic hammer at the lower right provides scale.Photo by Jim Luhr, 2000 (Smithsonian Institution).

The Colima volcanic complex consists of the massive overlapping edifices Nevado de Colima (the highest point of the complex to the right) and Volcán de Colima (left). Volcán de Colima was constructed within a 5-km-wide caldera that opens to the south and has been the source of large debris avalanches. Frequent historical eruptions have included dome growth, explosive activity, pyroclastic flows, and lava flows.

The Colima volcanic complex consists of the massive overlapping edifices Nevado de Colima (the highest point of the complex to the right) and Volcán de Colima (left). Volcán de Colima was constructed within a 5-km-wide caldera that opens to the south and has been the source of large debris avalanches. Frequent historical eruptions have included dome growth, explosive activity, pyroclastic flows, and lava flows.Photo by James Allan, 1981 (Smithsonian Institution).

The Plaza de Toros tuff ring on the SE side of Isla San Luis is seen here from the east in 2000. Remnants of dacite lava flows are visible in the upper walls of the crater. Only a third of the tuff ring is still standing; the rest has subsided along normal faults or was eroded by wave action. Longshore currents have redistributed volcanic deposits to produce the tombolo to the upper right that forms the SW tip of the island and is 2 km long at low tide.

The Plaza de Toros tuff ring on the SE side of Isla San Luis is seen here from the east in 2000. Remnants of dacite lava flows are visible in the upper walls of the crater. Only a third of the tuff ring is still standing; the rest has subsided along normal faults or was eroded by wave action. Longshore currents have redistributed volcanic deposits to produce the tombolo to the upper right that forms the SW tip of the island and is 2 km long at low tide.Photo by Keith Sutter, 2000.

Volcán Ajusco, the highest peak of the Chichinautzin volcanic field, is seen here from the summit of the Xitle scoria cone to the NE. The Pliocene-Pleistocene Ajusco consists of lava domes surrounded by block-and-ash flows. During the Pleistocene the NE flank collapsed, producing a debris avalanche that traveled 16 km. Late-stage eruptions produced more mafic lava flows from flank vents, marking a transition to the monogenetic volcanism of the Chichinautzin volcanic field.

Volcán Ajusco, the highest peak of the Chichinautzin volcanic field, is seen here from the summit of the Xitle scoria cone to the NE. The Pliocene-Pleistocene Ajusco consists of lava domes surrounded by block-and-ash flows. During the Pleistocene the NE flank collapsed, producing a debris avalanche that traveled 16 km. Late-stage eruptions produced more mafic lava flows from flank vents, marking a transition to the monogenetic volcanism of the Chichinautzin volcanic field.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

The tower of the unfinished San Juan Parangaricutiro church rises above the lava flows that surrounded it in 1944. The Taquí lava flow began on 8 January 1944 from the SW base of Parícutin. Renewed lava extrusion on 24 April threatened the town of San Juan Parangaricutiro and impacted it 17 June. The church was surrounded by lava in July. By the time the flow ceased in early August it had a length of 10 km.

The tower of the unfinished San Juan Parangaricutiro church rises above the lava flows that surrounded it in 1944. The Taquí lava flow began on 8 January 1944 from the SW base of Parícutin. Renewed lava extrusion on 24 April threatened the town of San Juan Parangaricutiro and impacted it 17 June. The church was surrounded by lava in July. By the time the flow ceased in early August it had a length of 10 km.Photo by James Allan, 1985 (Smithsonian Institution).

The summit pinnacle of La Malinche is seen here from the south. The summit consists of several lava domes, one of which filled the vent from the last major eruption of the volcano about 3,100 years ago. Note the people in the left foreground for scale.

The summit pinnacle of La Malinche is seen here from the south. The summit consists of several lava domes, one of which filled the vent from the last major eruption of the volcano about 3,100 years ago. Note the people in the left foreground for scale.Photo by Renato Castro, 2000 (courtesy of José Macías, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

Trails of steam in the foreground rise from floating scoriaceous clasts during a submarine eruption off the west coast of Socorro Island in 1993. The eruption, from vents about 3 km NW of Punta Tosca, was first observed 29 January 1993 following ten days of SOFAR (SOund Fixing And Ranging) signals recorded in Hawaii. Large scoriaceous clasts up to 5 m in size floated to the surface without associated explosive activity. Floating masses of hot scoria were erupted until at least the end of February 1994.

Trails of steam in the foreground rise from floating scoriaceous clasts during a submarine eruption off the west coast of Socorro Island in 1993. The eruption, from vents about 3 km NW of Punta Tosca, was first observed 29 January 1993 following ten days of SOFAR (SOund Fixing And Ranging) signals recorded in Hawaii. Large scoriaceous clasts up to 5 m in size floated to the surface without associated explosive activity. Floating masses of hot scoria were erupted until at least the end of February 1994.Photo by Hugo Delgado-Granados, 1993 (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

This view shows the Popocatépetl summit crater floor towards the end of its 1919-1928 period of activity. The crater floor is occupied by a smaller crater about 150 m in diameter. After 1925, the activity of the volcano decreased dramatically and ended by 1927.

This view shows the Popocatépetl summit crater floor towards the end of its 1919-1928 period of activity. The crater floor is occupied by a smaller crater about 150 m in diameter. After 1925, the activity of the volcano decreased dramatically and ended by 1927.Photo by Dr. Atl (courtesy of José Macías, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

The San Quintín Volcanic Field on the NW coast of Baja California contains lava flows and young scoria cones. This view looks south from Volcán Basu to Picacho Vizcaino (surrounded by young lava flows), and Volcán Sudoeste (upper left). These are among the youngest features of the San Quintín field.

The San Quintín Volcanic Field on the NW coast of Baja California contains lava flows and young scoria cones. This view looks south from Volcán Basu to Picacho Vizcaino (surrounded by young lava flows), and Volcán Sudoeste (upper left). These are among the youngest features of the San Quintín field. Photo by Jim Luhr, 1990 (Smithsonian Institution).

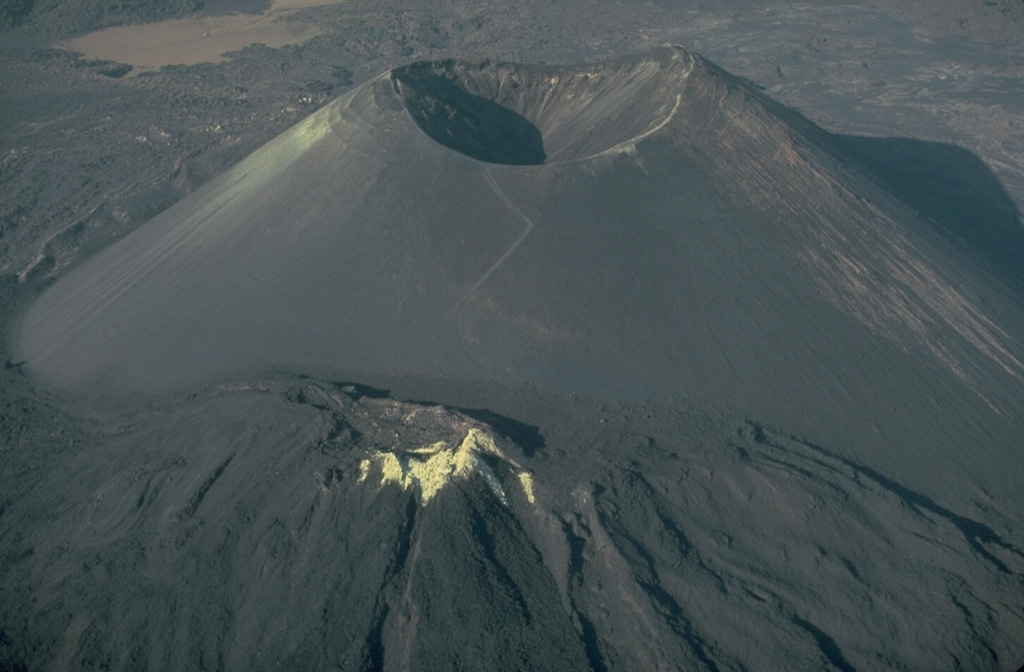

A 1941 aerial photo from the SW shows a dark lava dome that was extruded into the 450-m-wide crater created by the powerful explosive eruption of January 1913. In 1922 the crater floor had a depth of about 300 m and was covered by debris from the crater walls. By May 1930 the crater bottom lay about 150 below the crater rim, and when the crater was visited in January 1931 black lava was up to 50 m below the notch on the northern crater rim. Renewed dome growth in 1957 soon filled the crater and by 1961 lava began flowing over the crater rim.

A 1941 aerial photo from the SW shows a dark lava dome that was extruded into the 450-m-wide crater created by the powerful explosive eruption of January 1913. In 1922 the crater floor had a depth of about 300 m and was covered by debris from the crater walls. By May 1930 the crater bottom lay about 150 below the crater rim, and when the crater was visited in January 1931 black lava was up to 50 m below the notch on the northern crater rim. Renewed dome growth in 1957 soon filled the crater and by 1961 lava began flowing over the crater rim.Photo courtesy Julian Flores (University of Guadalajara), 1941.

A plume rises above the eastern side of the summit crater of Popocatépetl in December 1994. Ash deposits from previous eruptions darken the glaciers on the upper flank. This aerial view from the NE shows the El Ventorillo peak on the right-hand horizon, the remnant of an older edifice.

A plume rises above the eastern side of the summit crater of Popocatépetl in December 1994. Ash deposits from previous eruptions darken the glaciers on the upper flank. This aerial view from the NE shows the El Ventorillo peak on the right-hand horizon, the remnant of an older edifice.Photo courtesy CENAPRED, Mexico City, 1994.

The far western crater rim of Nevado de Toluca volcano is seen here on the horizon from the NE. The road into the crater is across the center of the photo below the low, smoother northern crater rim. The smooth surface of the northern flank consists of a lava flow that was modified by extensive Pleistocene-Holocene glacial erosion.